If You Want To Make A Difference (and a living), Please Don't Start Another Food Brand

An open plea to entrepreneurs and investors to look at the unsexy middle of the food system to make real change and, yeah, real returns

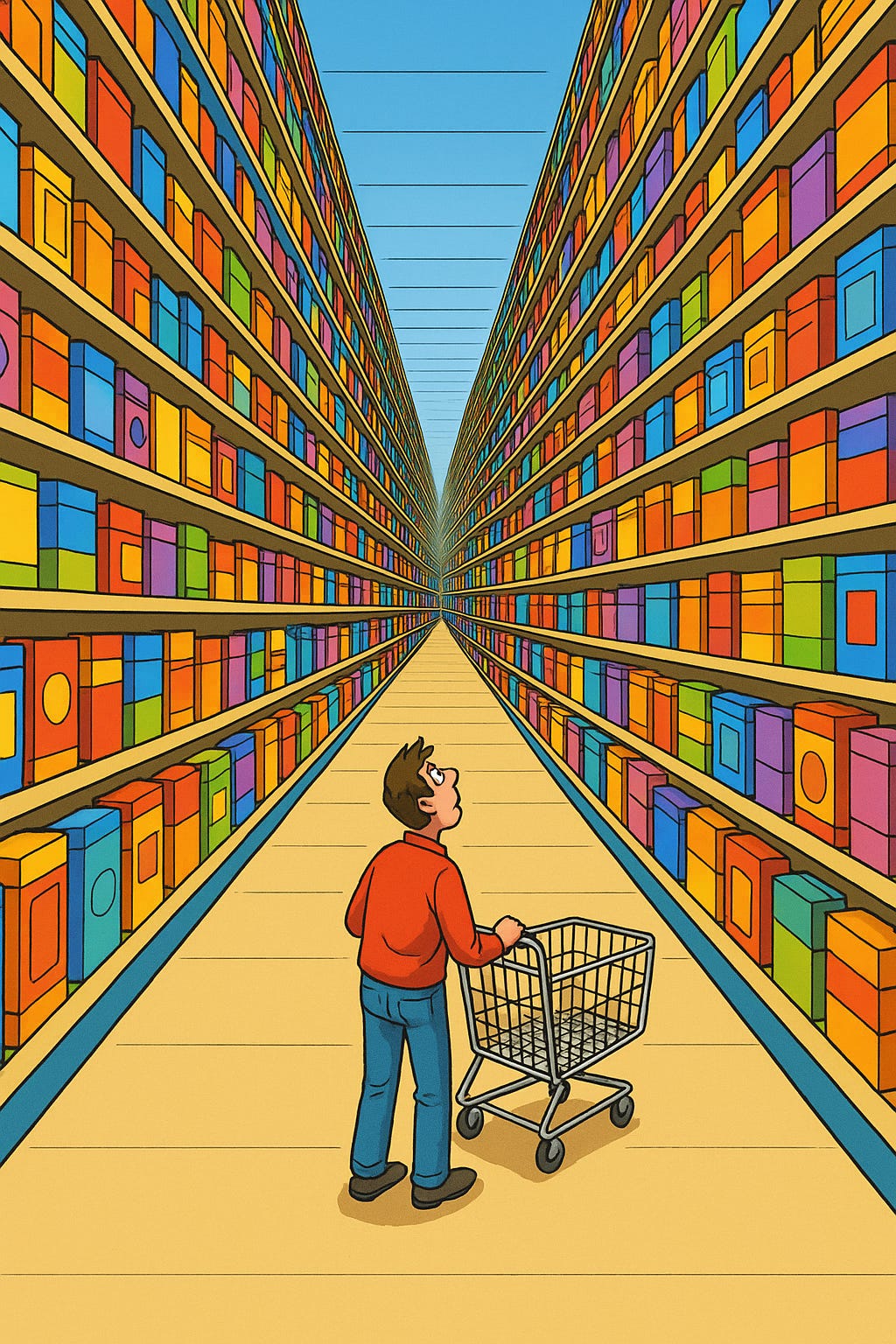

Every year, tens of thousands of new food and beverage products hit the market. From keto snacks to artisan hot sauces, grocery shelves and shiny Shopify websites are bursting with new F&B products vying for attention. The sad but true story is that a huge majority of these are bound to fail.

According to Nielsen data, a measly 15% of new CPG products survive more than two years, meaning 85% vanish within 24 months. In the ultra-competitive beverage category, an estimated 300 new brands launch annually with about a 90% failure rate, and fewer than 3% ever reach $10 million in sales. One study found roughly 80% of premium food/bev brands never even crack a cold million in retail sales. In short, the odds of creating the next KIND Bar or Vitaminwater are about as favorable as winning the Powerball.

They suck, these odds.

Why is it so ding-dang hard? For one, the market is saturated with choices, and big incumbents dominate shelf space. Customer acquisition is expensive (just ask Blue Apron). Margins in food are thin, and scaling up usually demands hefty marketing spend, broker fees, and slotting fees that drain cash. Even successful launches can stall out after initial hype. IRI found that of its “pacesetter” new products (the best-selling launches), more than half had vanished 2–3 years later.

Making a new brand stick is an uphill battle, even with great recipes and branding.

Please trust me on this one.

And I know you’re dying to try it. Your recipe is the one. Your idea meets an unmet and underserved market who is dying to give someone their money. But before you go sink your energy into yet another CPG food brand, maybe ask yourself if you could make a bigger difference (and paycheck) elsewhere in the stack.

Follow the Money

When you buy food, very little of your dollar actually goes to the farmer or producer. The USDA’s “food dollar” analysis shows that for every $1 US consumers spend on food, only ~7.8 cents goes to farmers. The rest is gobbled up by layers in the middle: food processors (12.6¢), retailers (12.5¢), distributors/wholesalers (4.9¢), restaurants/foodservice (a whopping 33.3¢), plus transportation, packaging, energy, and other supply chain costs. In other words, the middle of the value chain (everything that happens after raw ingredients leave the farm) captures well over 90% of the economic value.

This “messy middle” is where both the problems and the profits lie. Today’s food system is fundamentally a tangled web of middlemen.

Farmers are often price takers, while disproportionate margins accrue to the intermediaries – the distributors, brokers, packers, and market-makers who connect supply with demand.

By the time a product reaches you, it’s been marked up by transporters, processors, wholesalers, and retailers, each taking a cut. Value is leaking at every step in inefficiencies, waste, and added costs. By the end, the consumer pays a high price, the farmer earns a pittance, and there’s waste and inefficiency all over the floor in the middle.

Launching another branded sauce or snack or drink doesn’t change this equation; you’ll just be stepping into an overcrowded marketplace where the deck is stacked against you and most of the consumer’s dollar goes to middlemen, not your mission.

If you really want to move the needle, look at those middle layers that everyone else overlooks.

The Unsexy Middle

The irony is that the unsexy parts of the food business (distribution, logistics, supply chain operations, merchandising, category management) are exactly where an entrepreneur can make outsized impact (and solid returns). Improving the plumbing of the food system may not get you the Forbes article you can post on your LinkedIn, but it’s where huge opportunities lie.

Let’s talk cold storage for a hot minute. Lineage Logistics runs temperature controlled warehouses for food suppliers, living both up- and downstream of value added food production. They exist in the background and I never see them mentioned on LinkedIn where everyone is talking about probiotic soda and protein candy. But in 2024 Lineage went public at a valuation over $18 billion after growing to 482 cold-storage warehouses and $5.3 billion in revenue by relentlessly focusing on efficient food distribution. They had the largest global IPO in the world in 2024 and we’re still over here bubbling over Poppi? Yes, pun intended. That is a far bigger scale than almost any trendy consumer brand ever achieves.

Infrastructure may be less glamorous than branding a sexy beverage, but it scales dramatically when you solve a widespread pain point.

Even the big retail players recognize the power of supply chain innovation. Walmart and Kroger recently invested in building out their own milk processing plants, and Costco built its own poultry supply chain (from farm to rotisserie chicken). Not because they wanted to play farmer or factory, but because optimizing the midstream gives them better control and margins. These moves cut out inefficiencies and middle markups, saving costs and ensuring supply.

The point is, the real leverage in food is often in fixing the boring stuff: the packing plants, trucking routes, inventory systems, and distribution networks that get food from A to B.

Meanwhile, another 172 entrepreneurs have lost their shirts trying to sell creatine-infused pasta sauce just in the time it took you to read the last paragraph.

Does anyone remember Juicero? They made a $400 Wi-Fi connected juicer that basically just squeezed juice out of a bag. It was a slickly marketed Silicon Valley “food tech” play that raised $120 million from investors only to shut down 16 months after launch when customers discovered they could squeeze the juice packs by hand just as easily. Juicero is a punchline about overfunded consumer crap. A solution looking for a problem that, it turns out, didn’t exist.

Or Blue Apron, the meal-kit darling that did identify a consumer desire (convenient DIY gourmet meals) but struggled with the economics. Blue Apron had to build a brand and a complex cold-chain logistics operation to deliver fresh ingredients to doorsteps. They did grow rapidly and even IPO’d, but were never profitable, losing $55 million on $795 million revenue in one year.

Customer acquisition costs went through the roof; at one point Blue Apron spent $60 million on marketing in a quarter to barely grow subscribers. As competition flooded in, the business’s low margins and high churn caught up with it. By 2020, Blue Apron was scrounging for cash infusions to stay afloat.

In contrast, startups that tackle supply chain inefficiencies head-on can create real value quickly while flying well below the radar.

Afresh is a tech company you’ve probably never heard of, but it’s quietly helping grocers manage fresh inventory with AI. Grocery stores using Afresh’s system have cut fresh food waste by over 25% and boosted produce profit margins by 40% on average. That kind of improvement drops straight to the bottom line (and, AHEM, actually helps the planet).

It’s not flashy consumer marketing, it’s just a better system for ordering the right amount of bananas. But saving a supermarket chain 25% of its produce waste is incredibly impactful, both financially and environmentally. There are many such examples: from routing software that reduces empty miles on delivery trucks, to sensors that monitor cold storage to prevent spoilage, to B2B marketplaces that help farmers sell surplus crops instead of dumping them. These may never trend on Instagram or make the LinkedIn headlines, but they solve the real, costly problems plaguing our food system.

Where Entrepreneurs And Investors Can Actually Move the Needle

It’s time to rethink what a “food startup” can and should be. If you’re a founder or investor passionate about food, consider these high-impact opportunity areas in the middle of the value chain instead of yet another consumer brand:

Fight Food Waste & Spoilage: Over 38% of the U.S. food supply goes unsold or uneaten representing 88+ million tons of wasted food in 2022, worth about $473 billion. This is a massive efficiency failure that still doesn’t have enough solutions. Imperfect Foods, Misfits Market, The Ugly Company, and Hungry Harvest are a few branded plays on fighting food waste. The Conscious Pet is a pet food company that upcycles human-grade food for pets (also founders Mason and Jess are good friends and a lifelong mission-driven food people). Entrepreneurs can build systems to reclaim surplus (e.g. platforms to redistribute excess inventory), or technologies to extend shelf life and improve inventory rotation. Solving waste has direct ROI for businesses – as shown by Afresh’s 25% waste reduction stats – and consumers are increasingly on board with waste-reducing innovations. There is real money to be made saving food that would otherwise be tossed.

Smarter Distribution & Marketplaces: The long chain between farm and fork is rife with middlemen and markups. Farmers often get less than 10¢ on the dollar for their products, while grocers and distributors face unpredictable supply. Solutions that connect producers more directly to buyers or streamline the handoffs can create value for all sides. This could mean B2B marketplaces that let restaurants source straight from local farms, or digital platforms that replace a tangle of brokers with transparent pricing and logistics.

Logistics & Cold Chain Optimization: Food logistics might not sound exciting, but consider that many distribution trucks run half-empty and supply routes are often archaic. Improvements here yield huge gains. Stock-outs alone cost retailers nearly $1 trillion globally in lost sales each year. There’s demand for startups that optimize trucking routes, warehouse management, and cold storage utilization. The success of a giant like Lineage Logistics shows how lucrative it can be to focus on moving and storing food efficiently. Whether it’s sensors and data analytics for better routing or shared cold storage services for small producers, logistics innovation is a goldmine of cost savings.

Supply Chain Software & Data Transparency: The food industry’s backbone runs on surprisingly dated infrastructure. Think clunky ERP systems, faxed orders, and siloed data from farmers to factories to retailers. This lack of connectivity means producers are flying blind about real consumer demand, and distributors can’t easily adjust to supply shocks. Modern, cloud-based software that brings visibility to the supply chain, and its deployment and implementation, is desperately needed. Opportunities abound for inventory optimization tools, traceability systems, and data platforms that give all players a shared source of truth (e.g. demand forecasts, inventory levels, in-transit tracking). By empowering smarter decisions (and enabling things like recall tracing or dynamic pricing), these tools can save millions and reduce risk. Food supply chains are complex, but a well-built software platform can tame that complexity.

Co-Packing & Manufacturing Services: Many aspiring food founders actually don’t want to run their own factories, they rely on co-packers. But co-packers often operate at capacity, with long waitlists and high minimum orders that squeeze out small brands. There’s an opportunity for businesses that expand manufacturing capacity or offer flexible, scaled-down production services for emerging brands. For example, a startup could create a network of on-demand kitchen or manufacturing facilities, or build a marketplace to better match brands with available co-packer capacity (Keychain just raised $15mm and I’m watching them to see if there’s a real market for their matchmaking service). Solving these bottlenecks helps hundreds of brands go to market faster and cheaper. The demand is certainly there, it’s just a matter of unlocking it.

Retailer & Distributor Opex Modernization: I don’t even know where to start talking about the fat that is trimmable here. Switching to digital price tags in retail is already saving millions in labor and materials and quickly passing on savings to customers. Merchandising and category management are still mostly running on stone-age processes and too heavily-laden with people. Builders and investors should take aim at these roles as well as over-bloated finance departments that could more easily and seamlessly run on modern systems.

Each of the areas above addresses places where value is leaking out of the system: food rotting in landfills, money lost to needless intermediaries, trucks wasting fuel on inefficient routes, or factories sitting idle while would-be makers wait in line.

By plugging these leaks, you not only do good (for farmers, for consumers, for sustainability), but you can build highly scalable, profitable businesses. Companies and customers will beat a path to your door if you can save them money or headaches in the supply chain. And unlike a fickle consumer brand, a supply chain business often enjoys reliable B2B revenue, higher margins, and defensible niches once you develop expertise or networks.

Think Beyond the Brand

To be clear, it’s not that consumer food brands can’t ever succeed or make an impact.

Obviously they do. Just look at massively sexy and successful brands like Yellowbird Foods (AHEM use code substackbird for 14% off your first order).

But those stories are the rare exceptions. For every success, hundreds of other brands fail or limp along, never achieving the scale to really move the needle on health, sustainability, or access. The food system’s biggest challenges today aren’t that we lack enough chip brands or flavored seltzers; it’s that we waste absurd amounts of what we produce, and struggle to efficiently get food to the people who need it. It’s that farmers and small producers can’t get fair value, while consumers pay premiums that mostly fund supply chain inefficiencies. These are not problems a new protein bar will solve.

So I’m challenging you all to put your entrepreneurial energy into the infrastructure of food; the nuts and bolts that actually deliver calories from farm to table.

You can have a far greater impact.

It might mean building something that isn’t customer-facing at all, and that’s okay.

Not every great business is a consumer brand.

Maybe repeat that a few times.

The middle of the food chain may lack glamour, but it offers real chances to innovate, create value, and even achieve those outsized financial returns that attract venture investment, if that’s your cup of tea.

So, next time you feel the itch to launch “the Uber of vegan cupcakes” or “an artisanal soda for gamers,” take a step back. Ask yourself: Do we really need this, or would my talents be better used fixing a broken link in the food system?

The actual truth is that another brand of snack or sauce isn’t going to change the world.

But a breakthrough in food distribution, logistics, or waste reduction just might. The entrepreneurs who embrace these less-traveled paths will not only dodge the crowded graveyard of failed CPG brands, they’ll also be the ones driving actual food innovation forward.

If you want to make a difference (and build a lasting business), please don’t start another brand.

Instead, go fix what’s lurking behind the scenes: that’s where you can feed both your wallet and your soul.

i love to look to the food market from your different perspective: you are giving so much food for thought ! well i’m in Belgium so many examples are not known. But i agree on the innovation on the food chain especially to reduce waste. We have here quite successful companies like Too good to go that are specialising in selling out at reduced prices food that is going to be discarded ( wasted ). In a way it is a part of a business model, but still profitable.

There is no argument that most startups, not just CPG brand startups, fail. But why brush aside someone's aspirations to bring something they love (and may just want others to love) into the world? Maybe they simply enjoy the process of bringing that certain something into the world (win or lose). I truly admire what you have accomplished with Yellowbird. It's been an inspiration to me. The challenges and opportunities you have outlined here are certainly valid, but these are challenges that require tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars of capital to address. Suggesting that folks should focus on solving those problems rather than pursuing something they love is the wrong approach. I'd love to engage with you on ways these challenges/opportunities can and should be addressed sometime.